This CWG Memorial commemorates ‘over 4,700 Indian and Nepali soldiers and labourers who lost their lives on the Western Front during the Great War, and have no known graves’.

‘Inspired by Emperor Ashok’s inscribed columns of the 3rd century BC, the column is surmounted with a Lotus capital, the Imperial British crown and the Star of India. Two tigers are carved on either side of the column, guarding the temple of the dead’. (cwgc.org)

As we approach Remembrance Day, Jason Beckett, BACSA’s Cemetery Records Officer, writes about Indian Army memorials from World War I:

‘On a chilly November morning in 1914 a small figure braved the cold to inspect the newly arrived troops at St Omer in Northern France. This would turn out to be Lord Roberts of Kandahar’s last inspection. Fred Roberts was born in Cawnpore. He had been an officer in the Bengal Artillery and won the VC in 1858 during the Indian Mutiny. Through the second half of the 19th century, he commanded British and Indian troops in India, Abyssinia and Afghanistan.

At the age of 82 he was determined to visit these troops as they were the Lahore Division, part of the Indian Expeditionary Force.*

These Sepoys, Havildars, and Jemadars had travelled from places such as Sindh, the Punjab and Nepal to the cold fields of France. They, and many more like them, went on to fight in terrible battles such as Ypres and the Somme and further afield in the heat and dust of Mesopotamia, Egypt and East Africa.

Today some might be surprised to find out that regiments with exotic names like Cureton’s Multanis, the Scinde Rifles, Ludiahana Sikhs and the Bhopal Infantry fought amongst the shrapnel and barbed wire of the western front alongside Tommy Atkins. These men encountered some of the worst fighting; writing home to their distant families they described their experiences: ‘The shells are pouring like rain in the monsoon’ declared one. ‘The corpses cover the country, like sheaves of harvested corn’, wrote another.

One of these young men was Gabar Singh Negi. He was born in the small Himalayan village of Manjaur on 21 April 1895. In October 1913 he enlisted, joining the 2nd Battalion, 39th Garwhal Rifles.

The Garwhal Rifles joined the Indian Expeditionary Force, assigned to the Western Front. They saw action in October 1914 when they fought at the First Battle of Ypres.

Gabar and his comrades fought in the Battle of Neuve Chapelle, assaulting the German lines around the village. His Battalion attacked the southwest of Neuve Chappelle on 10 March. The preceding artillery barrage had not been effective, and the German trenches were still strongly defended. Gabar was in one of the parties who were ordered to take these trenches. His commander was killed, so Gabar took control, continuing to lead from the front until the trench was taken. Gabar was killed in the attack. For his actions, he was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. Gabar (‘Gobar Sing Negi’) is commemorated on Panels 32/33 of the Neuve Chapelle memorial.

Field-Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck, the future Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army, recognised the outstanding service provided by soldiers such as Gabar Singh Negi and asserted that the British ‘couldn’t have come through both World War I and II if they hadn’t had the Indian Army’.

Nearly 1.4 million men from India served in the Great War, some in non-combatant roles, making this the largest all-volunteer force the world had seen at the time.

The physical evidence of their struggle and sacrifice can be seen in the Memorials and Graves at cemeteries such as Neuville-Sous-Montreuil Indian Cemetery in the Pas de Calais region of France, Patcham Down Indian Forces Cremation Memorial in England and Dar Es Salaam British and Indian Memorial in Tanzania.

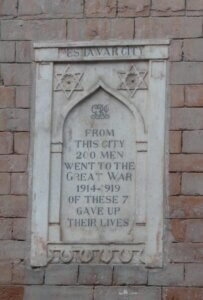

They are also remembered in their hometowns and cities. In the Northwest Frontier city of Peshawar, a small memorial in the centre of the old walled city commemorates the 200 men who volunteered for the war and the 7 who never came back. In Karachi a large cenotaph stands marking the sacrifice made by over 650 men from the Baluch Infantry who fought and died in France, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia and Palestine.

who ‘gave up their lives’ out of the

200 who ‘went to the Great War

1914-1919’.

Located on the Cunningham clock

tower, in the centre of the old

walled city. (Photo: Jason Beckett)

Mary’s Own Baluch Light Infantry, who

fought in ‘France, Egypt, East Africa,

Mesopotamia, Persia, NW Frontier of

India, Palestine’.

Located near Frere Hall.

(Photo: Jason Beckett)

In Kolkata there are two war memorials on the city’s Maidan: The Glorious Dead Cenotaph, dedicated to British and Anglo-Indian soldiers who lost their lives in World War I, and the Lascar War Memorial which honours the 896 lascars who also died during the War.

Kolkata

(Photo: Kinjal Bose 78)

Kolkata

(Photo: Rangan Datta Wiki)

By the end of the war over 74,000 Indian troops had lost their lives and a similar number were wounded. For their service and bravery, a total of 13,000 medals were awarded, including 12 Victoria Crosses.

On the 11th of November this year, when we remember those who for our tomorrow gave their today, we should include in our thoughts the 74,000 men from the old Indian Army who made the ultimate sacrifice’.

*Roberts died of pneumonia at St Omer, France, on 14 November 1914 while visiting Indian troops.

Jason Beckett, Cemetery Records Officer

****************************************************************************

(Suggestions for BACSA website news items, volunteering opportunities and diary entries, are always welcome – please send them to ‘comms@bacsa.org.uk’.)