This exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 2RL, which ‘celebrates the creative output and internationalist culture of the golden age of the Mughal Court (c.1560-1660) during the reigns of its most famous emperors: Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan’, runs until 5th May 2025.

Akbar r.1556-1605

Aged 14 when he became emperor, Akbar rapidly expanded his territory through conquest and diplomatic alliances.

to Shah Jahan in the presence of Jahangir’. Bichitr, c.1630

(Minto Album, Chester Beatty Library, Dublin)

Encouraging innovation and creativity, his court was supplied with luxury products made by craftsmen combining their traditional skills with elements of European art introduced by Jesuit missionaries from the Portuguese territory of Goa.

In 1578 Persian, already the language of the cultivated elite, was officially adopted as the administrative language of the empire.

Akbar died, aged 63, in 1605, and was buried at Sikandra, just north of Agra.

This allegorical 3-generation painting by Bichitr, created shortly after Shah Jahan’s succession, depicts Akbar, in the centre, handing the imperial crown over to his grandson Shah Jahan, in the presence of his son Jahangir.

A similar allegorical painting ascribed to Govardhan likewise depicts Akbar as the grandson, receiving the crown from his grandfather Timur, while his father Humayun looks on.

Jahangir r.1605-1627

Akbar’s son Salim Jahangir (‘Seizer of the World’) inherited a wealthy, stable territory, and continued his father’s practice of encouraging the arts.

(British Museum, London)

New master practitioners came to the court, from Iran and Europe; craftsmen in the imperial workshops experimented with new materials such as jade (from Khotan), and new techniques (like enamelling).

So dazzling was the appearance of Jahangir’s court that Sir Thomas Roe, England’s first ambassador to the Mughal emperor, described it as ‘The Treasury of the World’.

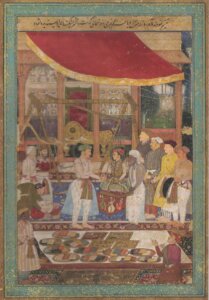

Created c.1614 for an imperial copy of the Jahangir-Nama (‘Jahangir’s memoirs’), this painting depicts Jahangir’s son’s first annual weighing ceremony (in 1607), following which an equal weight of precious materials would be distributed to the poor.

Once the prince had come of age, the weighing ceremony was conducted on his birthday each year, with the specially constructed jewelled balance – either indoors or outdoors, as appropriate.

c.1610-1620

(On loan from the al-Sabah Collection, Dar al-Athar al-Islamittah)

(V&A Museum)

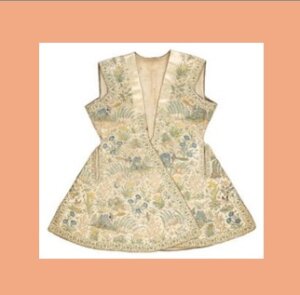

Embroidered in fine chain stitch on white satin, with images of flowers, trees, peacocks, wild cats and deer. The area round the neck is left free of embroidery, to enable a separate fur collar to be attached.

Chain-stitch embroidery of this type is associated with professional, male embroiderers of Gujarat, where they were employed to embroider fine hangings and garments for the Mughal court, as well as for export to the west.

Shah Jahan r.1628-58

Jahangir’s son Shah Jahan (‘King of the World’), who became emperor at the age of 36, developed a passion for architecture.

Bichitr, c.1628

(Minto Album, Chester Beatty Library, Dublin)

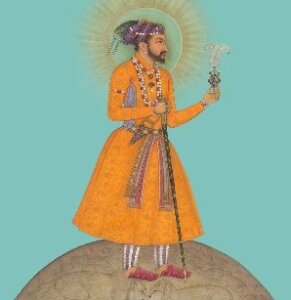

Depicted here in c.1628 as the ‘King of the World’, Shah Jehan suffered such intense grief after the death of his wife Arjumand Banu (Mumtaz Mahal) in 1631, that a third of the hairs on his dark beard reputedly turned white within a few days.

He designed the Taj Mahal as her mausoleum. Flowering plants carved on the walls, and inlaid on her white marble cenotaph, started a new trend with blossoms and floral motifs replacing traditional patterns on carved items and picture borders.

(V&A Publishing, 2024)

This exhibition is a wonderful opportunity to see a fascinating collection of items assembled from both the V&A’s own collection, as well as many other international museums and private collections.

For more information about the exhibition, please see the V&A website.

*************

(Suggestions for BACSA website news items are always welcome – please send them to ‘comms@bacsa.org.uk’.)

Rachel Magowan