‘Teatime at Peggy’s: A Glimpse of Anglo-India’, is the title of a book by Stephen McClarence and Clare Jenkins to be published by Bradt Travel Guides in June 2024. Here Clare describes the impressive restoration work at Jhansi Cemetery organised by the late Peggy Cantem and Captain Roy Abbott, prominent members of the Jhansi Anglo-Indian community.

The inscription on the tablet above the archway reads:‘This memorial gate was

renovated at his cost in 1995 by Capt. R. Abbott of the Royal Garhwal Rifles’

‘My husband Stephen McClarence and I first visited Jhansi cemetery more than 20 years ago, after meeting Captain Roy Abbott, the last British zamindar or landowner in India, known locally as the ‘Rajah of Jhansi’.

Abbott

(Photo: S McClarence)

Through him, we met Peggy Cantem, then in her late 70s, and the ‘Honorary Custodian’ of the town’s European cemetery: the ‘dead centre of the dead centre of India’ as she called it. Peggy became the focus of my 2015 Radio 4 documentary Teatime at Peggy’s – and of our book of the same title (to be published in June), detailing our encounters with Jhansi’s Anglo-Indian community.

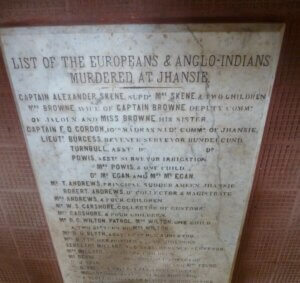

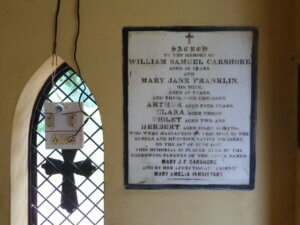

Jhansi cemetery is one of the country’s largest, covering ten acres and containing around 4,000 graves dating back to 1840. They include memorials to the 66 Jhansi-based British and European victims of the Indian Mutiny, sometimes including whole families. Among them were Arthur (4), Clara (3), Violet (2) and Herbert (eight months) Carshore who, along with their parents, ‘were massacred on this spot by the rebels and mutinous native soldiers on the 14th of June 1857’. The memorial, on a wall of the Victorian ochre-and-terracotta gatehouse, was erected by their mother’s ‘sorrowing parents’.

Europeans & Anglo-Indians

murdered at Jhansie’

(Photo: S McClarence)

members of the Carshore family

‘who were massacred on this spot’

(Photo: S McClarence)

Other graves reflect the town’s reputation as a ‘hardship posting’: British soldiers who had died of heat stroke, cholera or plague. The grave of Sergeant Major Arthur Horatio Barron of the East Surrey Regiment, who died in 1898, aged 33, is typical. ‘He tried to do his duty’ reads the simple inscription.

Ellen Moriarty (died in 1863, aged 27) shares a grave with her son Thomas (‘aged four hours’). A much later memorial to ‘Billy Boy‘, who died in 1946 aged five months, is inscribed ‘This little bird so young, so fair’. Lieutenant Roger Louis Gerard Wathen of the Royal Norfolk Regiment died aged 25 in 1935 ‘through an accident at polo’.

The occupants of some of the graves could never have anticipated being buried in India. When, in March 1938, an Air France plane flying from Calcutta to Jodhpur crashed and burst into flames near Datia, just north of Jhansi, all seven passengers and crew died and were buried here. Another grave is dedicated ‘In Everloving Memory of…’ Puzzlingly, the name was never added.

During our almost annual visits to Jhansi, Peggy’s ever-faithful auto-rickshaw driver, Anish, would drive the three of us to the cemetery, where her father, husband and eight-year-old brother Percy were all buried. She would proudly show us the work that had been carried out over the previous year, often with financial help from BACSA and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, as well as from Captain Abbott.

‘I want to give the dead the dignity they deserve’, she once told us, before explaining the reasons behind her ‘Operation Cemetery’ campaign: ‘I was once at a funeral there and saw a lady almost slip into a grave because the grass was taller than her, about six feet high. Someone said: ‘My God, this is the last place I’d want to be buried in!‘ And it struck me – ‘Peggy, do something for this place’. A lot of history is buried here. We should not lose our heritage’.

When she took over as custodian in 1984, the cemetery had been neglected for over 30 years: ‘It was thick with equatorial forestation’, she said. ‘It was worse than jungle! You just could not penetrate it. Huge palm trees and fronds from creepers were making it dark and dismal. It was frightening. No graves were visible, animals were destroying everything – hyenas, jackals, foxes, reptiles of all sizes. There were snakes falling on your head – once there was a huge python. I couldn’t believe it. I saw it going into a grave!’

(Photo: S McClarence)

The clearance project was expensive – over a lakh, or 100,000 rupees. ‘It costs 17,000 rupees a month for the staff alone,’ Peggy told us. The major problem was disposing of the (extensive) cleared foliage; bonfires couldn’t be lit in the cemetery due to the nearby army ammunition dumps. So she employed three men to keep the place clear, paying each of them 250 rupees a month, with a chowkidar (who lived on-site with his family) paid a similar amount.

Her vision, she said, was to create ‘a Garden of Remembrance and a tourist attraction’, raising the status of the cemetery to that of a heritage site for tourists visiting Jhansi Fort on their way to the erotic temples of Khajuraho.‘It’s one of the biggest parks in Jhansi,’ she said. ‘People love to come here in an evening. The peafowls are a glory in the evening. At sundown you will see them dancing and prancing all over the place. We have partridges and quails and wild hare: they are famous in this cemetery’. One patch of land was left untouched, specifically for the peacocks. ‘We call it their maternity ward because, after the rains, the peahens lay their eggs there. So I won’t let the staff touch that plot’.

On our first visit, in 2004, parts of the cemetery were well-maintained but, in others, the gravestones were swathed in creepers and banyan roots. Emerald-green parakeets squawked overhead as we wandered among memorials smothered by thickets of brambles, the scrubby ground scattered with debris. A blackened angel lurked in a thicket. It was a fascinating blend of death and life.

(Photo: S McClarence)

After renovation, the cemetery was considerably sprucer, albeit less romantic, with a water pump, lights installed to deter trespassers, flowerpots, shrubs and benches. The walls had been heightened, with barbed wire strung along the top, so the jackals could no longer jump over. ‘They were destroying the graves, ruining crosses, ruining plants. You used to hear them crunching the bones of the dead. Now that wildlife is gone, but we still have nilgai – huge fellows, colossal size. They look like deer but they are very aggressive’. Even she was amazed by the transformation. ‘We never knew we had so many people here!’ she said.

Many of Captain Abbott’s family were also buried there, including his wife Lillian and disabled daughter Penny, who died just two years apart. They were easily the best-kept graves in the cemetery: neat, whitewashed and with borders of pretty flowers. Next to them was an empty plot, marked ‘Reserved’. That became the final resting-place of the captain, when he died in 2017, the year after Peggy.

She had reserved her own plot next to her brother’s, who died in 1923, the same year she was born. ‘I’m going to make benches so that, after I die, I can see who goes and comes! Because then I can still go round in the night and see the work that is going on. That will be my job – to protect everybody there. I’ll make all the dead come along with me and have a walk. We’ll have a ball!’

Teatime at Peggy’s – a half-hour Radio 4 documentary about Jhansi’s Anglo-Indian community, is still available on BBC iPlayer: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b05tpwc7

The book Teatime at Peggy’s: A Glimpse of Anglo-India, by Stephen McClarence & Clare Jenkins, will be published by Bradt Travel Guides in June 2024.’

Clare Jenkins

Ed. note: As mentioned in Prof Peter Stanley’s recent post (13/4/24), memorial tablets from the Jhansi ‘domed chhatri’ Memorial were transferred to the gatehouse of Jhansi Cantonment Cemetery, for safeguarding, some years ago.

PDF copies of the BACSA 2019 cemetery record book Jhansi Cantonment Cemetery by Martin Smith, a ‘fully indexed directory of over 2,900 individuals interred at Jhansi Cantonment Cemetery prior to Indian Independence in 1947’, may be purchased through the Shop facility on the BACSA website.

Rachel Magowan