(Photo: TCC)

display

(Photo: R Dohmen)

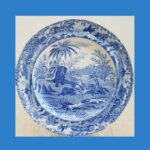

Around 20 BACSA members recently spent a very convivial evening at the home of Rosemary Raza, BACSA’s Events Officer, enjoying an informal presentation on Indian-themed blue and white china. The talk was given by Sue Norman, a long-established dealer with a passion for her subject.

Passing round a selection of beautiful items from her personal collection, Sue led us gently through the cultural and technological developments that underpinned the production of this very popular tableware.

near Allahabad

Thomas & William Daniell

Secondly, artists like Thomas Daniell RA (1749-1840) and his nephew William Daniell RA (1769-1837) travelled round the ‘Orient’, sketching the exotic places they found. After touring north India from Calcutta to Srinagar, and spending time in Madras, they returned to England and, between, 1795 and 1808, produced a 6-volume work entitled ‘Oriental Scenery’.

This was followed, in 1810, by ‘A picturesque Voyage to India by way of China’, which included views of the Bay of Bengal and the landscape bordering the river Hoogly.

(Photo: TCC)

Prints by landscape artists inspired designs showing views, buildings and scenes from everyday life in a very different part of the world. Plants and animals were often added to this backdrop – as were people wearing ‘eastern’ apparel; perhaps on horseback, or riding a camel – or even an elephant.

Meanwhile publications such as ‘Oriental Field Sports: Being a Complete Detailed and Accurate Description of the Wild Sports of the East’, written in 1807 by Captain Thomas Williamson, with drawings by Samuel Howitt, sparked interest in tropical wildlife pursuits: Spode’s ‘Indian Sporting Service’, launched c.1810, included a large platter with a picture entitled ‘Driving a Bear out of Sugar Canes’, a vegetable dish and cover, and a small platter, with ‘Hunting a Buffalo’, a sauce tureen with ‘A Dead Hog’, dinner plates with ‘Death of the Bear’, side plates with ‘Common Wolf Trap’ and soup bowls with ‘Chase after a Wolf’.

(Photo: Bonhams)

After the talk, several members of the group rounded off the evening with a meal at a local Indian restaurant. Our thanks are due to Rosemary Raza, BACSA, for organising, and hosting, a very enjoyable event; to Sue Norman, for preparing such an informative presentation, and bringing along so many beautiful items to illustrate it; and to Marcela for discreetly ensuring the hospitable flow of drinks and nibbles.

Rachel Magowan