Gwalior, Jhansi and Maharajpoor

This is the fourth in a series of posts by Prof Peter Stanley, the distinguished Australian military historian, who recently visited several historical sites in India gathering material for his forthcoming book (John Company’s Armies: the Military Forces of British India 1824-57).

This post covers places Prof Stanley visited in Gwalior, Jhansi and Maharajpoor. Posts about his visits to the Landour, Roorkee and Dehradun area, to Lucknow, and to Kolkata, Barrackpore and Serampore were published on 18/1/24, 12/2/24 and 25/2/24 respectively. A future post will cover his visit to Agra.

Gwalior

‘After meeting a group of history postgraduates from Jadavpur University, Kolkata (one of the main centres of academic military history in India), I flew from Kolkata to Gwalior, in Madhya Pradesh.

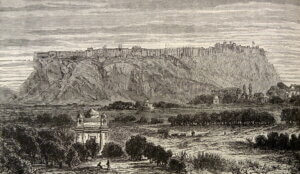

Gwalior is dominated by the great fort which fell to Sir Hugh Rose’s force in the Central India campaign during the hot weather of 1858. Its dramatic entrance was the site of the daring assault led by a couple of British officers of the Bombay Army.

‘This contemporary engraving from Edward Nolan’s The Illustrated History of the British Empire (1860) shows the challenge it represented for Rose’s attacking forces in 1858. Two British subalterns actually gained entrance by boldly forcing about eleven gates leading up a ramp on the fort’s NE face’ (P Stanley)

Jhansi

Staying in Gwalior allowed me to travel by rail to Jhansi, 100 kilometres south, and the location of another fort captured by Rose’s force; another battlefield. The fort (like Gwalior’s) is now under the protection of the Archaeological Survey of India, which provided gratis an informative brochure on the site. It confirmed that (as its appearance suggested) the victors after its capture had erected a typical British barrack bungalow atop a five-story Mughal palace, known as the Panch Mahal (‘the five-storeyed building’), a bizarre conjunction.

(Photo: P Stanley, 2023)

The brochure also disclosed that close to the fort was a memorial to the British dead of the 1858 siege. Finding the British memorial entailed a long, hot tramp through a street of car repair workshops, but eventually revealed a memorial, in an enclosure technically under the protection of the Archaeological Survey of India.

The memorial, a domed ‘chhatri’, is in poor repair, stripped of the inscriptions which once explained its purpose. Whether the enclosure holds the graves of British troops killed in 1858 is unclear – the brochure refers to a ‘cemetery’, but there is now no sign of individual or even mass graves. It offers a sad reminder of how little interest modern India takes in the history of the colonial power. What its future may be is uncertain.

(ASI) sign for the ‘Protected

Monument’ + ‘Memorial Cemetery’

(Photo: P Stanley, 2023)

Memorial to ‘The British dead of

1858′ (ASI)

(Photo: P Stanley, 2023)

Maharajpoor

From Gwalior I was also able to travel 40 kilometres north, to the battlefield of Maharajpoor. In 1843 the Governor-General Lord Ellenborough had intervened in a Mahratta dynastic dispute which saw a brief one-week war. Two British armies advanced on Gwalior to fight two battles on 29 December, at Punniar south of Gwalior and at Maharajpoor north of the city. At Maharajpoor a 5000-strong British army advancing from Agra defeated a larger Mahratta force in which British and sepoy regiments attacked and took several strongly held villages.

I found the battlefield mostly covered by the town of Morena (which had been a tiny settlement in 1843 but was now the district headquarters). However, the ground over which Colonel Thomas Valiant’s brigade (HM 40th and 2nd and 16th Bengal Native Infantry) had attacked the village of Shirkapoor remained cultivated, as it had been in 1843. The brigade formed up virtually on what became the route of the Agra-Gwalior railway line. The battlefield was unexceptional, but confirmed the discipline of British infantry needed to advance over a thousand yards of dead-flat farm land before engaging in bayonet fighting, a reminder of the nature of Indian combat in the mid-nineteenth century.

Maharajpoor had links with several places connected with my trip. In Kolkata I had visited the Gwalior Memorial on the Strand beside the Hooghly, built by Ellenborough soon after the battles and commemorating the British and Indian dead of the brief campaign, and I had been unable to view the memorial plaque in the grounds of Flagstaff House at Barrackpore. In Agra, where I travelled the next day, I found in St George’s church (in the cantonment), a memorial plaque erected by HM 39th Regiment to its dead, an officer and 41 other ranks (all named) who had died at, or because of, Maharajpoor.’

Peter Stanley

Ed. note: Some years ago the memorial tablets at the Jhansi ‘domed chhatri’ Memorial were transferred to the gatehouse of Jhansi Cantonment Cemetery, for safeguarding. PDF copies of the BACSA 2019 booklet Jhansi Cantonment Cemetery by Martin Smith, which includes transcripts of their inscriptions, may be purchased through the Shop facility on the BACSA website.

A future post by Clare Jenkins and Stephen McClarence will cover the impressive restoration work at Jhansi Cantonment Cemetery (‘The Dead Centre of the dead centre of India’), organised by the late Peggy Cantem and Captain Roy Abbot, prominent members of the Jhansi Anglo-Indian community.

Rachel Magowan