BACSA’s 2020 Spring event was to be a visit to the Wallace Collection in London on 14 April to see the magnificent paintings in the exhibition ‘Forgotten Masters’. Sadly, like so much else in these troubled times, the escalation of the Coronavirus forced the early closure of the exhibition and the cancellation of our visit.

The exhibition focused on paintings, done in India, that were commissioned by European patrons from Indian painters in the period from the 1770s to about 1850. These have, in recent years, been called ‘Company’ paintings – a name coined by the art historian Dr Mildred Archer in 1972 from an old Urdu term used in Patna ‘Kampani Kalum’. The exhibition tried to get away from this description but the title of the exhibition is equally misleading. It suggests – most unfairly – that the magnificent paintings done by these painters were virtually unknown prior to the Wallace exhibition. Nothing could be further from the truth. There have been numerous exhibitions of such both in London and America. As far back as 1978 ‘Room for Wonder’ at the American Federation of Arts in New York, was curated by Stuart Cary Welch. It included many of the works displayed again at the Wallace and many others. There have also been a number of scholarly books written on the subject. The Wallace Exhibition was curated by the renowned historian William Dalrymple and the exhibition was generously supported by the Delhi Art Gallery.

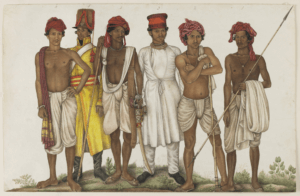

Despite the shortcomings of the title, this was a stunningly beautiful exhibition and included some of the finest works ever created in India during the period. For me the highlights were the eighteen superb paintings commissioned by James and William Fraser in Delhi and Haryana in the years around 1815-17. Their collection only came to light in the late 1970s and was sold in two sales at Sothebys in 1979. These figure studies are an unrivalled record of Indian life in and around Delhi. They were mostly done by one or more artists closely associated with Ghulam Ali Khan and indeed these artists may have been of his immediate family. A few of the Nautch girls were almost certainly done by the peripatetic artist Lalji or his son Hulas Lal – the father had apparently studied under Johan Zoffany in Lucknow in the 1780s and later both father and son were to migrate to Patna. These folios are now widely distributed in public and private collections so it is even more remarkable that so many could be reassembled for this exhibition.

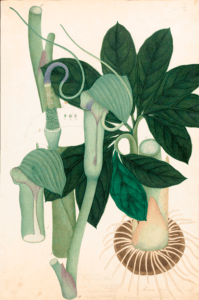

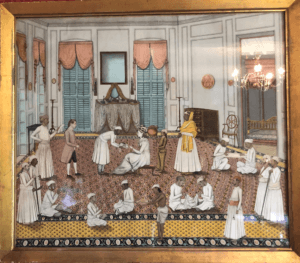

Long before the British and other Europeans started to commission paintings from Indian artists there had been a strong tradition of painting in the Muslim Courts of Upper India. With the gradual decline of patronage from the Imperial Court in Delhi artists migrated to Faizabad (and after 1775 to Lucknow), Patna and Murshidabad and adapted their styles to the requirements of the local courts. With the sudden rise in the influence of the British some of these artists again migrated to Calcutta. In the late 1770s the Chief Justice, Sir Elijah Impey, and his wife, both having a keen interest in painting, commissioned three remarkable painters to create some of the most breathtakingly beautiful and accurate large images of birds on branches, native animals and reptiles that exist anywhere. All three artists – Shaikh Zain-al-din of Patna, a Muslim, and Bhawani Das and Ram Das, both Hindu – used a meticulous and highly skilled technique to render onto paper every detail of a bird’s plumage or each hair on the back of a magnificent animal. Yet despite working in what must have been unfamiliar territory at the outset, each artist retained his Mughal sensitivity to his subject. Two paintings of interior rooms in the Impey house have – rather unconvincingly – been attributed to Zain-al-din. They are works of the highest order and among the greatest ‘Company’ paintings known to us. A generation later the Scottish surgeon Dr Francis Buchanan-Hamilton employed a barely known Bengali artist, Haludar, to draw a great variety of animals and reptiles from monkeys and bears to the smallest rodents – his two skittish field mice return the viewer’s gaze with a whimsical stare. Malini Roy’s essay on Haludar in the catalogue is much the most original and informative.

The last room of the exhibition focused on perhaps the finest Murshidabad landscape painter of his age – Sita Ram. He travelled extensively with Marquess Hastings from Murshidabad to Agra and painted lively atmospheric scenes along the way. They provide us with vivid images of the landscapes and buildings and his approach seems to have been influenced by the coloured aquatints of William Hodges in the picturesque quality. They were brought back to England in ten albums, two of which were dispersed in the 1970s and the remainder acquired by the British Library some twenty or so years ago. Sadly his work was inadequately represented, with two albums displayed in glass cases and only one painting hung on a wall, a fascinating scene of the Great Mughal gun beneath the Shah Burj at Agra. It was left to Jeremiah Losty’s scholarly essay on Sita Ram to redress the balance and provide a proper insight into his achievements.

The exhibition provides many wonders – though as one who knows the field, I was disappointed by omissions. Where are the quirky studies of Fakirs done for Jonathan Duncan in Benares, the fascinating scenes of Hindu and Muslim festivals by the Patna painters Sewak Ram and Bhavani Baksh, the quirky paintings from the Malabar Coast and the breathtaking paintings by Nevasi Lal from Lucknow. Nevertheless, the sheer quality of the exhibits that were on view and the excellent scholarship in the catalogue essays, made the exhibition worthy of more than one visit.