Where the Lion trod – the British lion that is – was the title of one of the first books about the history of the British in undivided India. Published in 1960, thirteen years after the last British soldier had walked through Bombay’s Gateway of India quay-side arch, Gordon Shepherd’s light-hearted ‘political travel’ book was an affectionate summary of British rule.

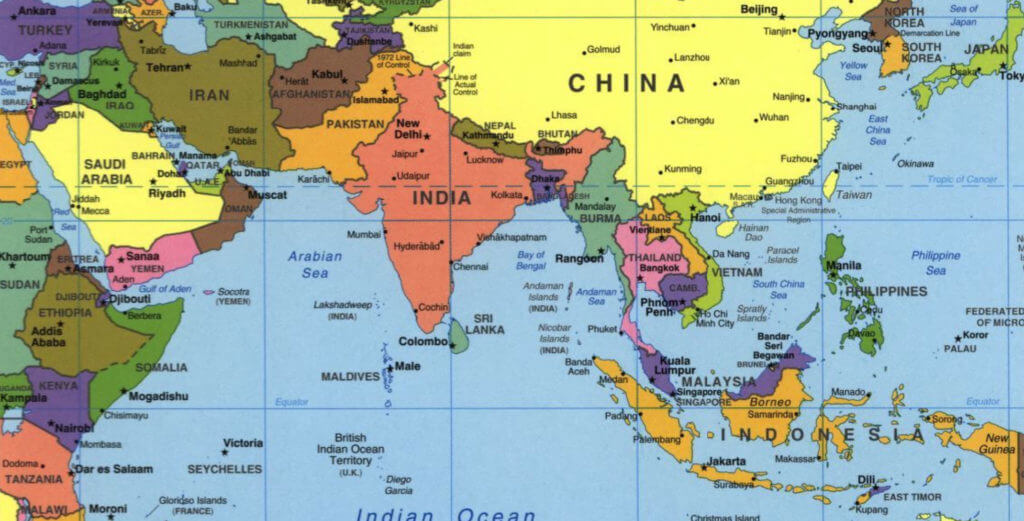

BACSA’s remit follows the lion’s paw-prints and covers those areas where the English East India Company set foot, and which were later to become part of the British Raj. It is a much wider area than one imagines but let’s start with India. It was at the end of 1600 that a group of merchants, meeting in London, petitioned Queen Elizabeth I to allow trading to the East Indies, an area that covered South East Asia as well as the Indian sub-continent.

The first ships brought home rare spices like nutmeg, peppercorns, cloves and cinnamon and by 1612 the Company had won permission from the Mughal Emperor to establish a small trading post at Surat, on India’s west coast. It was called a ‘factory’ and the men who worked in it were known as factors. Their job was to collect Indian goods for export to the West and to sell British goods in India and countries further east, including China.

Two more small factories were set up at Bombay and Madras and because of the valuable items stored in them, awaiting shipment or distribution, security guards were needed. So local men were recruited and trained to British military standards. They were called sepoys (the Indian word for soldiers) and in time these small units of men developed into the East India Company’s own army, that was quite separate from British regiments in India.

Portuguese and Dutch merchants were already trading in the same areas as the British, although the Portuguese became unpopular with the Mughals because their Jesuit priests had an aggressive policy of forcible conversion to Christianity. The English East India Company avoided religious interference and remained strictly secular until the beginning of the 19th century. It was able to take over the old Portuguese trading routes and ports, including the small market town of Calcutta with its Bengali and Armenian merchants. Here another ‘factory’ was established inside a fortified area built on the east bank of the Hughli river.

The story of how the English Company fought off its European trade rivals in India, including the French, and became landlords and revenue collectors for the fading Mughal Empire is one that has often been told, most recently by BACSA member William Dalrymple in The Anarchy: the Relentless Rise of the East India Company (published in 2019).

Although many of the men who worked for the Company did so to make money and hoped to survive long enough to return home to enjoy it, there were scholars among them too. People like Sir William Jones, a skilled linguist who was appointed judge of the Supreme Court in Calcutta. He was taught Sanskrit by Indian pandits and founded the Asiatic Society of Bengal to study India’s history, culture and manufactures. The oldest such society in the world it still exists today on the corner of Park Street and Chowringhee in Calcutta. Other skilled men included botanists like Colonel Robert Kyd, adventurous officers like Captain John Smith who rediscovered the Buddhist Ajanta caves in western India and Sir Stamford Raffles who founded modern Singapore.

Trade led to Company establishments along China’s eastern coast, notably at Canton and a number of smaller ‘treaty ports’ including Shanghai and Ningpo. Around the Arabian peninsula small trading posts grew up at Mocha and Aden, while Baghdad and Jeddah had Company men as Consuls and Vice-Consuls. As early as 1763 a Company Residency was opened at Bushehr, in the Persian Gulf, and relations with Persia remained relatively stable. On the other hand, the first Anglo-Burmese war in the 1820s led to the annexation of substantial parts of that country while the Company suffered a significant defeat after an ill-fated excursion into Afghanistan which led to an humiliating retreat from its capital, Kabul, in 1842.

So the areas that BACSA covers are extensive and the people too – not only British citizens who died in South Asia, but other Europeans too. People flocked eastwards from the late 16th century, beginning, as we have seen, with the Portuguese, and followed by the Dutch, the Danes, the French, and even a small contingent of Swiss. The graves of German and American mariners are found particularly in Burma and Macau. Armenian and Jewish traders were already well-established in the Indian sub-continent, as their ancient churches and synagogues remind us. As European men mingled with local women, a sizeable Anglo-Indian population developed too. At present there are no associations similar to BACSA in other European countries although there have been individual efforts to restore cemeteries including the ‘Swiss’ cemetery at Seringapatam, where members of the de Meuron family are buried, and the Dutch cemetery at Chinsura, in Bengal.

During the early 19th century the Company lost control of its trading role and abandoned its secular position. The ‘Indian Mutiny’, known today as the Great Uprising, was the final blow when a number of local grievances led to the Company’s sepoys rebelling and killing their British officers. This quickly escalated into general unrest in parts of northern India, particularly across what is today Uttar Pradesh. When order was restored in 1858 the British Government took over the territories formerly administered by the Company and installed its own Political Agents in the areas still under local rule. This was the start of the British Raj that lasted until 1947, when India gained Independence and the separate state of Pakistan was created.

Burma became independent a year later and other areas, formerly under British control, because they had once been part of Company territory, slipped away. Malaya gained its independence in the 1950s and the Yemeni port of Aden was one of the last to leave in 1967 – a reminder of just how far the old British lion had trodden.

BACSA’s remit covers a wide geographical area